After a plot of ice sent Marc Durocher rushing to the ground, and the doctors of the Umass Memorial Medical Center repaired the broken hip resulted in the 75 -year -old electrician found himself at a crossroads.

He no longer needed to be in the hospital. But he was still suffering, unstable on his feet, not ready for independence.

Patients at the national level often stall at this intersection, stuck in hospital for days or weeks because nursing homes and physical rehabilitation facilities are full. However, when Durocher was ready for the release at the end of January, a clinician came with a surprising path: you want to go home?

More specifically, he was invited to join a research study at the UMASS Chan Medical School in Worcester, Massachusetts, to test the concept of “SNF at home” or “Subaiguë at home”, in which the services generally provided in a qualified surveillance technology are offered at home, with visits to remote treatment and technologies.

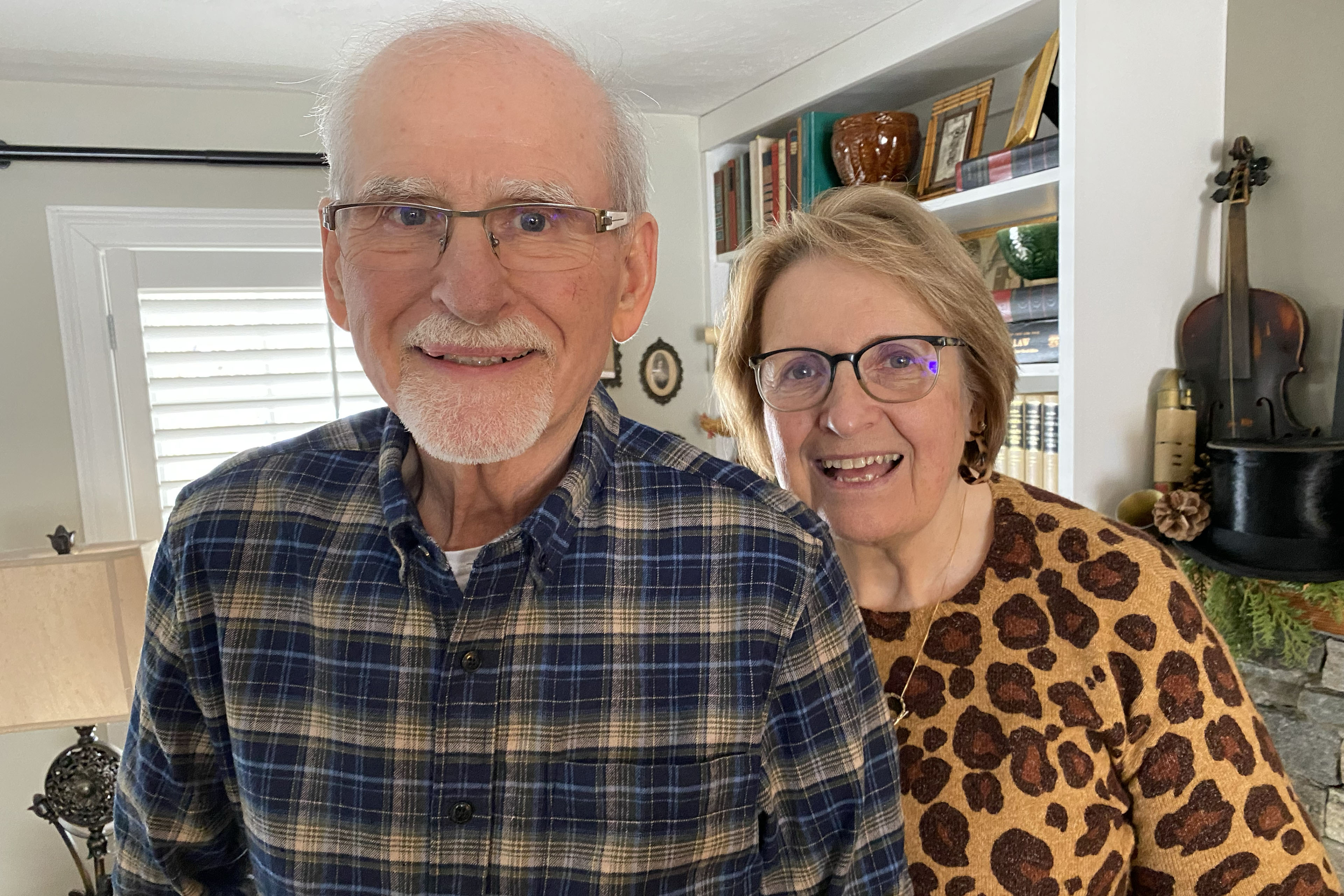

Durocher hesitated, fearing not to get the care he needed, but he and his wife, Jeanne, finally decided to try him. What could be better than recovering at home in Auburn with his dog, my friend?

Such rehabilitation at home is underway in various regions of the country – notably New York, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – as a solution to a shortage of nursing homes and rehabilitation beds for patients too sick to go home but not sick enough to need hospitalization.

Staff shortages in post-Aiguës establishments in the country led to a 24% increase over three years of hospital stay in patients who need qualified nursing, according to a 2022 analysis. Without where to go, these patients occupy costly hospital beds they do not need, while others wait in emergency rooms for these places. In Massachusetts, for example, at least 1,995 patients were waiting for the hospital in December, according to a Hospitals survey by the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association.

Providing intensive services and remote monitoring technology can operate as an alternative – especially in rural areas, where nursing homes are faster pace that in the cities and relatives of patients must often travel far to visit. For patients from Marshfield Clinic Health System who live in rural regions of Wisconsin, the clinical SNF-to-home program is often the only option, said Swetha GudibandaMedical director of the Hospital Program at home.

“It will be the future of medicine,” said Gudibanda.

But the concept is new, an outgrowth of hospital services at the house extended by a derogation from Pandemic inspiration Covid-19. SNF-to-house care remains rare, lost in a tax and regulatory world. No federal standard explains how to manage these programs, which patients should be eligible or what services to offer. No reimbursement mechanism exists, therefore health insurance and most insurance companies do not cover these care at home.

The programs only emerged in some hospital systems with their own insurance companies (such as the Marshfield Clinic) or those who organize “grouped payments”, in which providers receive fixed costs to manage an episode of care, as can happen with the Advantage Medicare plans.

In the case of hardocher, care was available – at no cost for him or other patients – only by the clinical trial, funded by a subsidy of the State Medicaid program. State health officials have supported two simultaneous studies at UMASS and Général de Mass Brigham, hoping to reduce costs, improve the quality of care and, above all, facilitate the transition of patients outside the hospital.

The American Health Care Association, the commercial group of for -profit nursing homes, calls “SNF at home” an improper term because, by law, such services must be provided in an institution and meet detailed requirements. And the association stresses that qualified nursing facilities provide services and socialization that can never be reproduced at home, such as daily activity programs, religious services and access to social workers.

But patients at home tend to get up and move more than those of an establishment, accelerating their recovery, says Wendy MitchellMedical director of the UMASS Chan clinical trial. In addition, therapy is adapted to their family environment, teacher to patients to sail in the stairs and the exact bathrooms that they will eventually use.

A quarter of people entering nursing homes suffer from an “unwanted event”, such as infection or wound, said David LevineClinical Director for Research for the Masse General Brigham Health Program at home and the leader in his study. “We are causing a lot of trouble in care-based care,” he said.

On the other hand, in 2024, no patient in the Contessa Health rehabilitation care program, based in Nashville, developed a bed of bed and only 0.3% fell with home infection, according to internal business data. Contessa provides home care thanks to partnerships with five health systems, including the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, the Allegheny Health Network in Pennsylvania and the Wisconsin Marshfield clinic.

The Contessa program, which provides post-hospital rehabilitation at home since 2019, depends on the help of unpaid family caregivers. “Almost universally, our patients have someone living with them,” said Robert MoskowitzInterim president of Contessa and chief doctor.

However, the two studies based on Massachusetts have patients who live alone. In the UMASS trial, a one -night home health assistant can stay a day or two if necessary. And although only patients “have access to a single button to a living person in our command center,” said APURV SONIAssistant Medicine Professor at Umass Chan and the head of his study.

But SNF at home is not without dangers, and choosing the right patients to register is essential. The UMASS research team learned an important lesson when a patient with light dementia has been alarmed by unknown caregivers who come to their house. She was readjusted in the hospital, according to Mitchell.

The study by Général de Masse Brigham relies strongly on technology intended to reduce the need for highly qualified personnel. A nurse and a doctor each lead a home visit, but the patient is also monitored remotely. Medical assistants visit the house to collect data with portable ultrasound, portable radiography and a device that can analyze blood tests on site. A machine the size of a toaster oven provides medication, with a robotic arm that drops the pills in a distribution unit.

The UMASS test, this one, has registered to Durocher, rather chose a “light touch” with technology, using only a few devices, said Soni.

The day Durocher returned home, he said, a nurse met him there and showed her how to use a wireless blood pressure cap, a wireless pulse oximeter and a digital tablet that would transmit her vital signs twice a day. In the coming days, he said, the nurses came to take blood samples and check it. Physiotherapists and occupational therapists provided several hours of treatment every day, and a home health assistant came a few hours a day. To his pleasure, the program even sent three meals a day.

Durocher learned to use the walker and how to climb the stairs to his room with a crutch and support from his wife. After only a week, he went to less frequent physical therapy at home, covered by his insurance.

“Recovery is incredible because you are in your own environment,” said Durocher. “To be relegated to a chair and a walker, and at the beginning someone who helps you get up, or go to bed, you shower – it’s very humiliating. But it’s comfortable. It’s at home, right?