Cops on ketamine? Largely unregulated mental health treatment faces obstacles

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting “988.”

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — A few months ago, Waynesville Police Sgt. Paige Shell was about to give up hope of getting better. The daily drip of violence, death and misery from nearly 20 years in law enforcement has left a mark. Her sleep was poor, depression was a stubborn companion, and thoughts of suicide took hold.

Shell, which operates in a rural community about 30 miles west of Asheville, tried talk therapy, but it was unsuccessful. When her counselor suggested ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, she was skeptical.

“I didn’t know what to expect,” she said with a gentle smile. “I’m a police officer. It’s a matter of trust.”

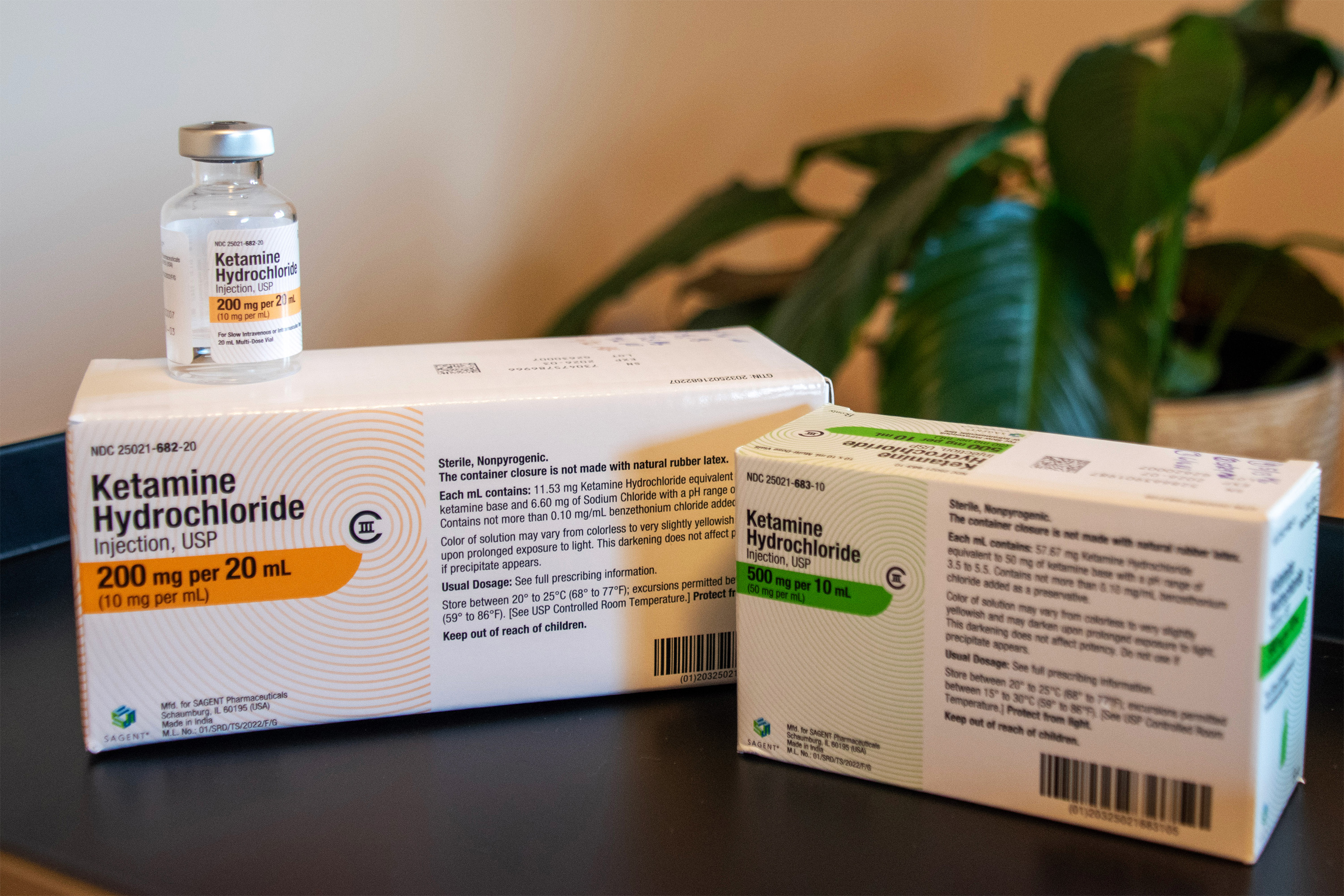

Combining psychotherapy with a low dose of ketamine, a hallucinogenic drug long used as an anesthetic, is a relatively new approach to treating major depression and post-traumatic stress, especially in populations with high trauma rates such as firefighters, police officers, and military personnel. However, the evidence on the effectiveness and safety of ketamine for treating mental health conditions is still evolving, and the market remains widely unregulated.

“First responders face a disproportionately high burden of trauma, and are often left without many treatment options,” said Signy Goldman, a psychiatrist and co-owner of . Medicine and psychiatry in Asheville, which began including ketamine in psychotherapy sessions in 2017.

Law enforcement officers in the United States, on average, experience 189 traumatic events during their careers, a A small study indicatescompared to two to three in the average adult’s lifetime. Research shows that rates Depression and fatigue We are Much higher among police officers compared to the civilian population. In recent years, more officers have died by suicide than killed in the line of duty, according to the first responder advocacy group. First help

Ketamine is a dissociative drug, meaning it makes people feel disconnected from their bodies, physical environment, thoughts, or emotions.

The Food and Drug Administration approved its use as an anesthetic in 1970. It became a popular party drug in the 1990s, and in 1999, ketamine was added to the list of Schedule III non-narcotic substances under the Controlled Substances Act.

“Friends” actor Matthew Perry died in 2023 Due to the use of ketamineWhich led to the drug’s reputation being discredited.

But starting with a 1990 Animal study Followed by a teacher Human trialResearch has shown that low doses of ketamine can also quickly reduce symptoms of depression. In 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved esketamine — derived from ketamine and given as a nasal spray — to treat treatment-resistant depression.

All other forms of ketamine remain FDA-approved for anesthesia only. If it is used to treat psychiatric disorders, it should be prescribed off-label.

“This is a situation where clinical practice may be ahead of the evidence to support it,” he said. John Crystalchair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine and a pioneer in ketamine research.

Crystal has Impact lesson of ketamine on veterans and active-duty military personnel—a similar number to first responders in their trauma exposure. While research shows strong evidence of ketamine’s antidepressant effects, he said more studies are needed on its potential role in treating PTSD.

Crystal said the regulatory environment for ketamine remains a concern. State oversight varies, and federal regulations do not specify dosages, routes of administration, safety protocols, or training of providers.

In this organizational patchwork, more than 1000 ketamine clinic It spread throughout the country. Home ketamine treatments have flooded the market, prompting the Food and Drug Administration to take action Issue a warning.

Ketamine side effects can range from nausea and high blood pressure to suppressed breathing. The medication can also cause adverse psychological effects.

“Taking the drug puts people in a very vulnerable state,” Goldman said. People can become re-traumatized when they recall upsetting memories. That’s why it’s so important for a mental health provider to guide a person through a ketamine session, she said.

With proper precautions — and when other treatments fail — Rick Baker believes ketamine-assisted psychotherapy is well-suited for first responders. Baker is the CEO and founder of Responder Support Services, which provides mental health treatment exclusively to police officers, firefighters and other first responders in North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee.

First responders, as a population, are more resistant than civilians to traditional treatment, said Baker, a licensed clinical mental health counselor. Ketamine provides a potential shortcut to traumatic memory and acts as an “accelerator for psychotherapy,” he said. “It strips people’s armor off.”

When used to treat mental health, a dose of ketamine — typically half a milligram per kilogram of body weight, less than anesthesia — creates a state of slightly altered consciousness, Goldman said. This makes people view their traumatic memories from a distance and “tolerate them differently,” she said.

Ketamine sessions at her clinic typically last two hours, and clients are on the drug for about 45 minutes. The medication is given by intravenous drip, intramuscular injection, sublingual lozenges, or combination nasal spray. The medication is short-acting, meaning its dissociative effects largely wear off within about an hour.

But most insurance companies won’t cover the cost of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, which can exceed $1,000 per IV drip session.

“This is definitely a no-no for first responders,” Goldman said.

Department of Veterans Affairs Covers some forms of ketamine Treatment, including ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, is provided to eligible veterans on a case-by-case basis.

In Shell’s case, a donation to Responder Support Services covered what her insurance didn’t cover when she decided this spring to try ketamine-assisted psychotherapy with her counselor, Baker.

Revisiting the most horrific calls of her nearly two decades as a police officer was not something Shell wanted to do. Hurricane Helen, which caused catastrophic flooding in western North Carolina last year, pushed the 41-year-old “over the edge,” she added.

“Some of the sessions were difficult,” said Shell, who is also a member of her agency’s SWAT team. “Things have come up that I didn’t want to think about, that I’ve buried all my career.”

The severely disfigured victim of a fatal car accident. A murder-suicide, in which a man slits his pregnant girlfriend’s throat and then slits his own throat.

Under the influence of ketamine, she said, the images came back to life as still images, like a surreal slideshow replaying some of her darkest memories. “Then I’ll sit there and cry like a baby.”

As of early October, Shell had undergone 12 ketamine sessions. She said they did not provide a sudden miracle cure. But her sleep has improved, and the bad days are now bad moments. She also finds it easier to manage stress. “And I’m smiling more than I did before,” she said.

She was reluctant to share her experience within her department because of the persistent stigma associated with seeking help in a difficult police culture.

“I didn’t want my colleagues to think I couldn’t handle this job,” she said. “I didn’t want them to feel like I was a danger to them.”

Perception of ketamine also plays a role, said Sherry Martin, the center’s national director of health services Fraternal Order of Policean organization that represents more than 377,000 sworn law enforcement officers. Many cops are familiar with ketamine as an illegal street drug, or think of it as a countercultural drug, she said.

“So, when they are supposed to accept this as treatment, it is difficult for them to understand,” she said.

Few, if any, police departments provide clear guidance on ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. If prescribed medically, it would likely be viewed like taking antidepressants, Martin said.

Eventually, Shell shared her story with her colleagues, most of whom were curious and supportive, and she now encourages other officers to talk about their struggles. She believes that seeking mental health treatment — in her case, ketamine-assisted psychotherapy — has made her a better, safer police officer.

“It’s hard to help others when you can’t take care of yourself,” she said.

Post Comment